Analysis of Current Trends in the U.S. Market

L.A. Marina: business is good. Towing company: no cargo

The trajectory of the American shipping market this year has been somewhat unusual, particularly in recent weeks. The same question can yield vastly different answers from different individuals. Even within the same market, perceptions can vary significantly.

Various data sources (LA/LB Port Authority, PIERS, Datamyne) indicate that the cargo volume at the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach surged nearly 30% year-on-year in the first quarter of this year, marking a sharp turnaround from last year’s slump and outpacing all other major U.S. ports. With such a rapid recovery in cargo volume, one would expect local trucking businesses to thrive.

But what is the actual situation?

Recent conversations with friends in the trucking industry operating in Los Angeles paint a different picture. Almost universally, they report encountering difficulties: prices are down, and there’s no significant uptick in cargo volume. From small firms with just a few trucks to large-scale trucking companies with thousands of units, all are facing challenges. On one hand, we hear the port authorities’ triumphant reports, while on the other, the struggling trucking companies are left wondering: where is all the cargo going?

The Los Angeles Port Authority has released a three-week forecast of cargo discharge volumes. While the data for the current week is quite accurate, the figures for the following two weeks are subject to adjustment. Instead of focusing on the total volume, let’s examine the flow of cargo.

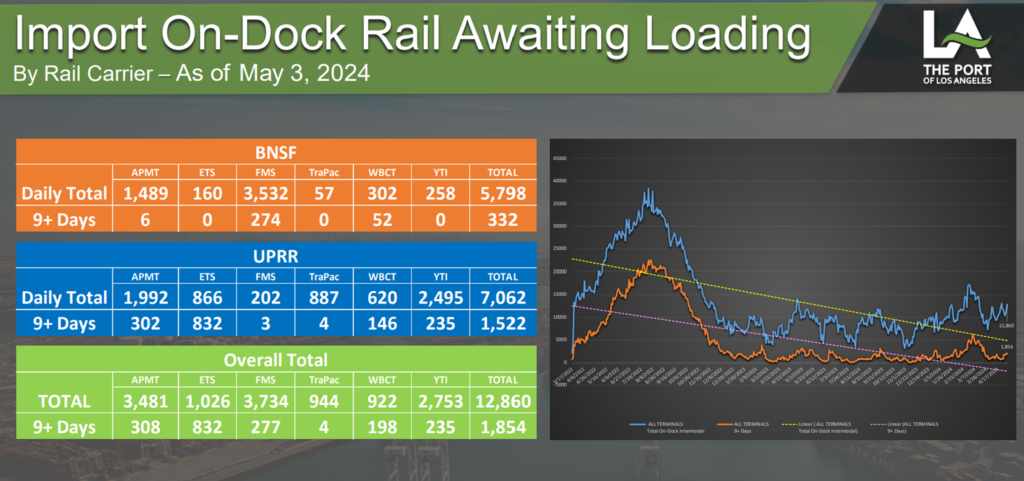

I’ve calculated that nearly 35% of the weekly cargo discharge volume is destined for inland points by rail, whether on-dock or off-dock. As mentioned in previous articles, the volume of Intermodal (IPI) cargo has been notably increasing since the beginning of this year, a trend that continues to this day and is expected to persist.

Generally, IPI cargo accounts for around 30% of a vessel’s total load. During the pandemic, delays in IPI cargo resulted in a drop in its proportion to as low as 10% of total cargo for several months. Now, while the current 35% proportion isn’t the highest in history, it’s still around 5% higher than the average. Using the port of Los Angeles as an example, an additional 5% of IPI cargo translates to a reduction of 5000 TEUs of local cargo per week. The situation is similar in the Port of Long Beach, where the combined effect results in a weekly reduction of 10,000 TEUs flowing into local warehouses.

Furthermore, considering the expansion of local trucking companies during the pandemic, it’s not a matter of fewer companies but rather an oversupply of services, leading to price compression in the trucking market.

Intermodal (IPI) cargo volumes have remained consistently high, but is there a delay in rail services?

According to the latest data, there are significant variations in rail service among terminals and railway companies. However, the overall situation seems manageable. About 15% of IPI containers at both port areas have been sitting for over 9 days without being loaded onto trains. Typically, it takes 4-5 days for containers to be loaded onto trains after discharge, except for expedited services. If we lower the threshold to 7 days or more, the proportion could exceed 20%. This situation is worse than off-peak seasons but better than during severe port congestion. Both major railway companies, UP and BN, are closely monitoring market changes and adjusting their railcar supply accordingly. However, railway companies often receive information about IPI cargo volumes late. If there’s a sudden surge in rail cargo volumes and railway companies are unprepared, it could worsen delays in IPI cargo. In such cases, some IPI cargo may be transloaded locally in Los Angeles, providing opportunities for trucking companies.

Source: Port of Los Angeles